Vachagan Malkhasyan/Shutterstock

If you’re becoming an audio geek, there’s a lot of terminology thrown around among audiophiles that may be a bit hard to follow without added context. If you’re new to how music is recorded, mixed, and mastered, there’s a lot to learn. One term that can get a bit confusing is how there’s more than one kind of audio measurement represented in RMS, short for root mean square. More broadly, root mean square refers to a mathematical equation that’s somewhat self-explanatory if you know what those terms mean, as it’s the square root of a number set’s mean square.

Advertisement

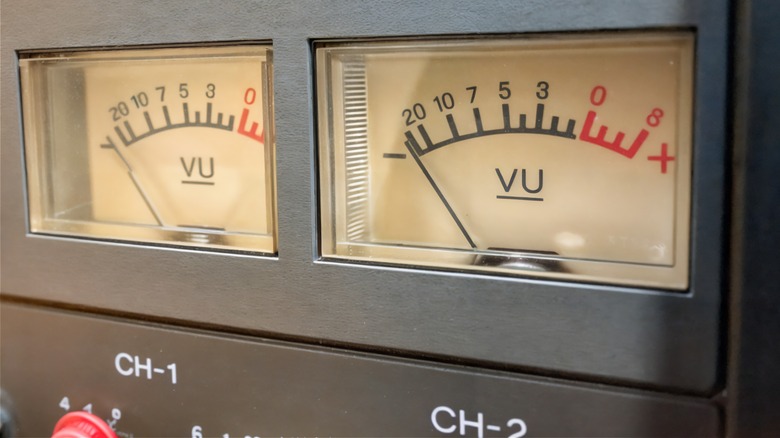

In audio, RMS can be used to represent two different things. One is a speaker or amplifier’s peak power rating, where, for example, a speaker rated at 150 watts RMS can safely handle a 150-watt continuous load. The other, perhaps more common usage of RMS in audio, comes in relation to dynamic range, the difference between the sounds in a given track with the highest and lowest volume.

In terms of dynamic range, RMS refers to the average loudness across an entire waveform, with loudness, in this context, referring to perceived volume. Two tracks could have the same peak volume levels, but the one with less dynamic range is going to be perceived as the louder of the two. This comes up most often as part of discussions of what was dubbed the «Loudness War.»

Advertisement

What was the Loudness War?

The Loudness War refers to the tactic of mastering music louder to make it stand out from other artists, originally with the goal of getting more radio airplay. At first listen, louder music sounds better to the average ear, so you can understand how this war started when it came to promotional singles intended for radio.

Advertisement

When vinyl records were the dominant music distribution format, this practice of compressing music to make it louder was kept in check, as overly loud music would make for defective records, with the stylus literally jumping out of a record’s grooves. CDs, however, don’t have this physical limitation, but they do have a hard peak level limit of 0 dBFS («full scale»). At first, CDs were mastered well below that level, but in time, the rise of home systems with multi-CD changers led to an increased desire to master music louder so it would jump out from other CDs.

Dynamic range compression, in and of itself, does not impact the overall fidelity of audio, and it can be used as a positive creative choice when enough care is taken. The problem is that such care was often not taken, and music would be squashed to such a degree that not only would songs become a lot blurrier, with less distinct elements in the arrangement, but it would also crash into the 0 dBFS limit, causing digital clipping that audibly distorted the music.

Advertisement

Examples of the Loudness War

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Though the Loudness War has settled down in recent years, it raged on for long enough that there are some albums that stand out for how egregious they were. Perhaps most the most infamous was Metallica’s 2008 album, «Death Magnetic.» According to the Dynamic Range Database, which collects measurements made using a dynamic range meter app released in response to the Loudness War, the entire «Death Magnetic» album averages just three decibels of headroom between the peaks and valleys in volume, with some tracks scoring a two.

Advertisement

Thankfully, though, there was a better version available from an unlikely source: The «Death Magnetic» DLC pack for the «Guitar Hero III» video game was sourced from before the audio was squashed, resulting in a far more pleasing dynamic range score of 12. Comparison videos on YouTube break down what this sounds like, with Lars Ulrich’s drumming being reproduced much more clearly in the video game version. In a contemporaneous interview with music magazine Blender, Ulrich, despite being the one whose contributions were most obscured in the final product, insisted that there was nothing wrong with the audio quality of the CD, but also conceded that their music was being mixed and mastered at extremely loud levels.

Advertisement

The Loudness War ended up being a key reason why more people listen to vinyl than CDs these days. The «limitations» of vinyl meant that it couldn’t be abused the same way, with Depeche Mode’s «Playing the Angel» being one example of how the CD version has major compression and clipping versus the vinyl version.