Mediterranean/Getty Images

Scotland has long been known as a nation of innovators. The Scots have had a hand in everything, from mammal cloning to the steam engine. Though the country is steeped in tradition and pride, it’s still given the world simple practicality when needed. Furthermore, the region has utilized its resources and is among the leaders on the European continent with regard to tidal energy developments, among other environmental projects.

Despite its often gray and miserable weather, the country has even added a bit of color to the world — color photography is a Scottish development. In fact, the first full-color photograph was a tartan ribbon. Almost everywhere you look and much of what you touch has a connection to Scotland in there somewhere. Don’t take my word for it, go and discover for yourself.

From golf to the toaster, there’s a lot more to Scotland than Mel Gibson screaming profanities at the English. The list of the country’s inventions and discoveries is a long one. One that would take ages to cover. But we’ve scraped a few together to take a better look at some that have shaped the modern world.

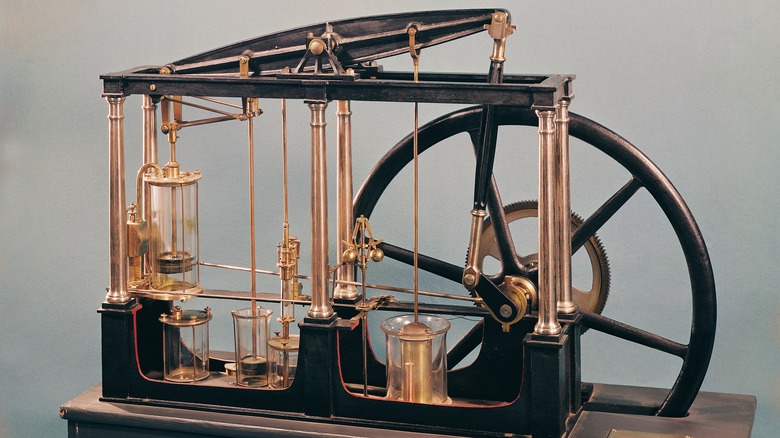

Revolutionary steam engine improvements

Art Images/Getty Images

James Watt, born 1736 in Greenock, Scotland, can’t be solely credited for the invention of the steam engine. However, it was his significant improvements in its efficiency in 1769 that helped fuel the Industrial Revolution. His most significant creation was the separate condenser, a distinct chamber where the steam was cooled and compressed away from the main cylinder. This innovation significantly reduced fuel consumption and energy waste.

The steam engine was primarily developed to support Britain’s lucrative coal industry. But since it was much more fuel-efficient and cost-effective, the technology was used in other sectors, such as cotton mills, factories, and tin and copper mines. It revolutionized manufacturing, transportation, and power generation and paved the way for other technological advancements throughout the 19th century. Watt’s engine was further improved with the addition of more robust iron fittings that minimized steam leakage from the piston.

He was also behind the expansion steam engine, which involved cutting off the heat source and allowing the steam to expand naturally. This saved even more on fuel and advanced railway transport costs. These enhancements led to even more powerful, versatile, and economical steam engines, such as the rotary motion engine, which could power flywheels. Along with his radical developments, James Watt also introduced the concept of horsepower. He used it to measure the output of his steam engines and as a marketing technique when convincing potential customers how many horses his engines could replace.

The chainsaw

Netris/Getty Images

The chainsaw was invented by Scottish doctor and obstetrician John Aitken around 1785. Soon after, another Scottish physician, James Jeffray, improved the design. You might be wondering what doctors and childbirth have to do with the cutting down of trees. Well, if you’ve ever watched a Hollywood slasher movie involving chainsaws, it probably comes as no surprise that the machine actually does have a somewhat gruesome history.

Aitken’s chainsaw was invented in 1785 to help improve symphysiotomy, a surgical procedure separates the pelvic joint during obstructed labor. Although it might not sound like it, it was much more preferable to caesarian sections, which were more life-threatening back then than today. Now, let’s get any images of wild-eyed, bloodthirsty doctors cranking up powerful chainsaws out of our heads. These early medical models were not fuel-powered — they were flexible, hand-cranked devices that featured fine serrated link chains and handles on both ends, allowing for precise cutting of the pelvic bone with minimal trauma to the surrounding tissue.

But let’s be thankful that modern medicine means surgery is no longer the stuff of horror movies, and women can focus on healthy childbirth without the need for such devices. Of course, medical breakthroughs didn’t mean the end of the chainsaw. In 1926, Andreas Stihl patented the first-ever electric chainsaw. Thankfully, it was to be used in the logging industry, and his eponymous brand is still a leading chainsaw brand today.

The macadam road

Alex_TP/Shutterstock

John Loudon McAdam — born in 1756 in the town of Ayr, Scotland — amassed a small fortune in the U.S. before returning to his home country and becoming a road trustee responsible for his local establishment. On considering the poor state of the highways around his hometown, he decided to experiment at his own expense to find ways to improve them. He continued with his tests under government appointment when he moved to Cornwall, England in 1798.

The result of his studies suggested that roads should be raised on beds to enable effective drainage. They also need to be covered with a base of large broken rocks laid out in patterns and then covered with smaller stones, with everything bound together by fine gravel or slag. The authorities were pleased with the results, and McAdam was given the job of Surveyor General of Metropolitan Roads in Great Britain in 1827.

These revolutionary techniques were soon introduced to other countries, particularly the United State, and immortalized MacAdam’s name in the perennial history of road building. Notably, the Boonsborough Turnpike in Maryland became the first macadam road in America. Another of those early routes brought together the parties negotiating the surrender treaty at the end of the Civil War.

Water-bound macadam roads served as a precursor to the tar-based binding that would go on to be known as tarmacadam, or tarmac as we call it now. The word is often used interchangeably with asphalt, but the latter is the more common and superior material now. It’s a bitumen-based binding that makes up 96% of the USA’s 2.3 million miles of road, per its Department of Transportation.

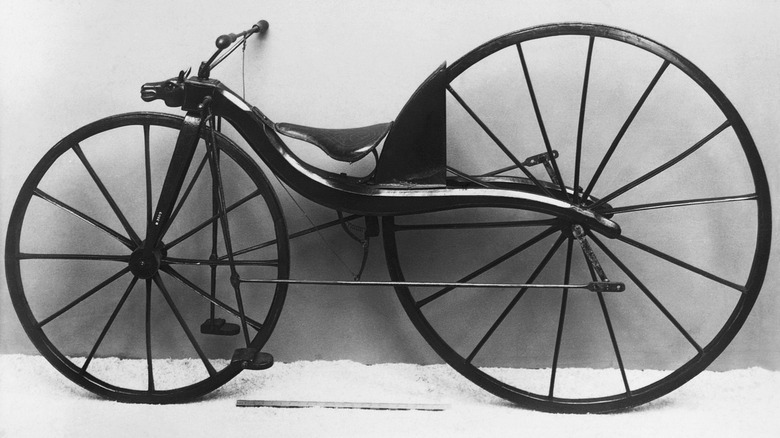

The pedal bicycle

Hulton Deutsch/Getty Images

Kirkpatrick MacMillan was a Scottish blacksmith born in 1812 in the small village of Kier Mill, Dumfriesshire. Other than the mill, this village isn’t particularly noteworthy for anything. Friendly locals and disagreeable weather are traits you can find in every Scottish village, town, and city. However, the citizens of Kier did witness the world’s first-ever bicycle with pedals, which MacMillan invented in his spare time way back in 1839.

As the story goes, Macmillan found the two-wheeled dandy horses people were riding at that time to be impractical. They were a crude form of velocipede that required the rider to propel themselves along by running their feet on the ground. Thus, MacMillan went to work with the goal of revolutionizing two-wheeled transportation. He presented the world (or at least his village) with his creation in 1839. He still needed to propel the bicycle by pushing his feet against the ground, but once in motion, the villagers watched in awe as he lifted his feet to the pedals and cycled along without his feet touching the ground.

It wasn’t an easy contraption to control. It certainly didn’t feature the gears found on modern bicycles, and at 57 pounds (27 kilograms), it was pretty heavy. Villagers darted out of the way as he sped through the village, but he was soon able to make it all the way to the town of Dumfries, some 14 miles away. Unfortunately, MacMillan made no money, and his invention brought no fame. He didn’t patent his work, and he is little remembered, even in his native Scotland.

The electric clock

Al Alex/Shutterstock

Known as the «father of electrical horology,» Alexander Bain, born in the parish of Watten, Scotland in 1810, is credited as the inventor of the electric clock. The first of his creations to be powered by electricity is still on display today at the Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow. Invented in 1943, the pendulum in this early Bain clock was powered by an earth battery consisting of electrodes buried in the ground to facilitate a small and stable electric current.

Bain went on to prove his clock could synchronize with others over long distances and act as a central timekeeper, a precursor to modern time networks. However, due to maintenance requirements and practicality issues, his model wasn’t widely adopted into households. Instead, it is remembered as a pioneering step in the evolution of electronic timekeeping.

He made significant contributions to telegraphy. Most notably, Bain invented an early form of the fax machine in 1843, which was then known as the electric printing telegraph. The device wasn’t widely used, but his technology was a platform for later models.

The pneumatic tire

Renovacio/Shutterstock

Robert William Thomson was born in 1822 in Stonehaven, Scotland and in 1845 was the first person to patent the pneumatic tire. He strove to improve long horse-drawn carriage journeys with a hollow leather design. Inside each tire was a rubber-coated fabric tube filled with air that was durable enough to last a 1,200-mile trip. Rubber was extremely expensive at the time, though — costs outweighed profits, and for almost 50 years, the pneumatic tire was put on the back burner. But in 1888, the invention made its long-awaited comeback.

John Boyd Dunlop, born in 1840 in Dreghorn, Scotland, independently developed and marketed his own version of the pneumatic tire, unaware of Thomson’s earlier patent. He eventually realized that Thomson, who had passed away some fifteen years prior, had already patented the concept. Nevertheless, Dunlop went on to market his design, initially to improve the bicycle. His company revolutionized two-wheeled transportation, but with these new fads called motor cars hitting the road, Dunlop Tyres was soon to make an even bigger name for itself.

The telephone

EWY Media/Shutterstock

Before we delve into this one, it’s important to note that Alexander Graham Bell is considered by many quarters to be a «Scottish-born» American-Canadian. However, in Scotland, he is very much considered to be «one of our own.» And that’s because he is.

Bell was born in Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland, in 1847. His Scottish parents raised him in the area around the famous Edinburgh Castle. He was already inventing at a young age, and by 12, he had invented a usable wheat dehusking machine on top of self-mastering the piano. He was educated at various institutions around his home country but eventually moved to Canada in 1870 at the ripe old age of 23. After obtaining citizenship there, he moved on to Boston in 1871.

So back to Bell’s most famous invention: the telephone. After his arrival in the Hub, he took up a position at the Boston School for Deaf Mutes (now the Horace Mann School for the Deaf). Together with his experiments with sound transmission, this set the stage for his finest hour. After teaming up with the skilled electrician and machinist Thomas Watson, the pair collaborated in electronic speech transmission experiments, which culminated in Bell’s immortal words and first-ever electronically transmitted speech in 1876: «Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you.» The inventor formed the Bell Telephone Company in 1877, and the rest is history. Landline telephones may well be considered obsolete technology nowadays, but his legacy lives on in cellphones.

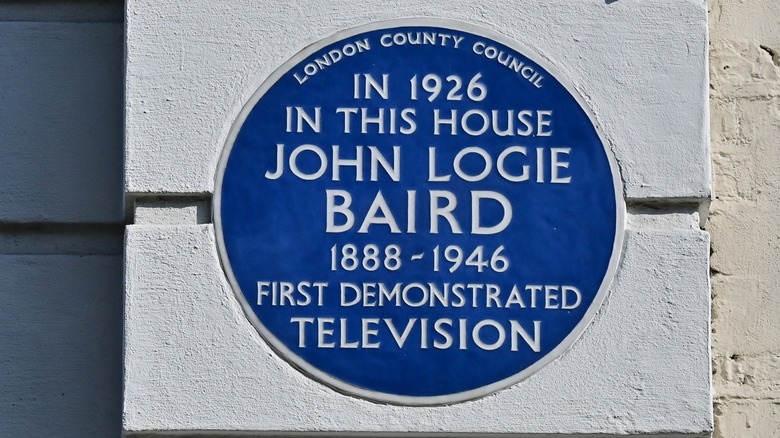

The television

Peter Moulton/Shutterstock

Another genuine world-shaping invention from Scotland was the television. It was invented by John Logie Baird, who was born in Helensburgh, Scotland in 1888. Many inventors can also be credited with substantial contributions, including German technician Paul Nipkow, Russian physicist Boris Rosing, and another Scot — engineer Alan Archibald Campbell-Swinton.

However, it was Baird who first gave the world a true television demonstration. It was delivered in the presence of 50 open-mouthed scientists in London in 1926. The Baird television was a truly odd-looking contraption, but by 1927 he delivered a 438-mile broadcast from London to Glasgow and formed the Baird Television Development Company. By 1928, London was transmitting to New York and even ships in the mid-Atlantic.

Baird surprisingly also gave demonstrations of color and even 3D broadcasts, with the latter being shelved for a considerably long period. It seems that some of these Scottish inventors were just too far ahead of their time. Of course, transmitting sound and images wouldn’t have been possible without Alexander Graham Bell’s mastering of electronic sound transmission some 50 years prior. The two signals were initially sent alternately, but by 1930, sight and sound were being sent simultaneously. After some years, electronic systems were being rapidly developed and began replacing Baird’s mechanical system. By 1937, the BBC, the world’s first television broadcaster, had dropped Baird’s method for Marconi-EMI’s all-electric system, which was more reliable and delivered better image quality.

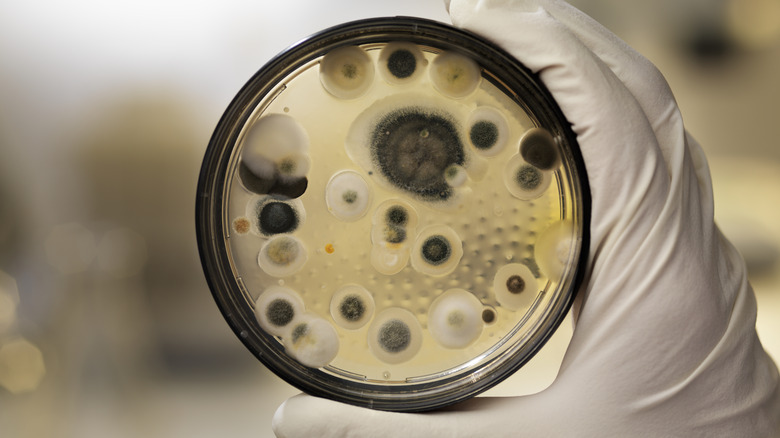

Penicillin

Andreasreh/Getty Images

While more of a medical breakthrough, the development of antibiotics, starting with penicillin, was crucial to the evolution of medical technology. Alexander Fleming, born in 1881 in Darvel, Scotland, discovered penicillin, and it’s an antibiotic that has saved the lives of millions of people worldwide. Not bad for someone who got his big break due to poor hygiene!

As the story goes, Fleming discovered the antibacterial enzyme lysozyme on a discarded petri dish in his cluttered laboratory. The substance was from his own mucus that he had left on the dish for a considerable time. He observed that the lysozyme inhibited bacterial growth but he eventually found it to be effective against only a limited number of species. But it did pave the way for the physician’s ultimate world-changing discovery.

In 1928, one of Fleming’s petri dishes began sprouting mold once more. Only this time, he was aware his lack of sanitation could have a positive outcome. Indeed, Fleming observed that the bacteria that came into contact with the mold met with an untimely end. He identified this mold as of the Penicillium genus and was very excited to find it had a disliking of gram-positive pathogens. In short, this mold could stop pneumonia, meningitis, gonorrhea, diphtheria, scarlet fever, syphilis, wound infections, and many other afflictions.

Per Singapore Medical Journal, the Nobel Prize winner himself was humble enough to admit, «I did not invent penicillin. Nature did that. I only discovered it by accident.» But his story tells us that scientific breakthroughs often come from the ability to recognize the significance of unexpected findings. That and not paying for a cleaner.

The automatic teller machine

Nature/Getty Images

The world’s first ATM was unveiled in 1967 by John Shepherd-Barron, born in British-colonized India in 1925 to Scottish parents. As reported by The New York Times, he received the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 2005 as recognition of being the «inventor of the automatic cash dispenser.» However, Shepherd-Barron’s machine wasn’t the PIN-fortified cashpoints we know today. Instead, his used cheques with an impregnated dosage of mildly radioactive carbon 14 that acted as the authenticator. It wasn’t particularly secure, given that anyone who stole the record could easily cash it.

James Goodfellow, born in 1937 in Paisley, Scotland, on the other hand, patented the PIN system and was just one month behind Shepherd-Barron with its launch. Goodfellow copyrighted his machine earlier in 1966 and despite it being licensed by most manufacturers, it was Shepherd-Barron that got all the credit. This overlooking was a thorn in Goodfellow’s side until he was finally recognized in 2006 as «patentor of the personal identification number,» per the BBC. He also now sits proudly alongside John Logie Baird and Alexander Graham Bell in the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame as the «inventor and first patentor of the automated teller.»