By Brad Hill/

The Italian submarine, the Scirè, wasn’t a large boat like some of the most advanced nuclear submarines in the ocean today. It only held a crew of 36, measured fewer than 200 feet in length, and was 21 feet wide. By comparison, a modern day American Ohio-Class submarine, the best unused weapon in the country’s arsenal, measures 560 feet long and houses over 150 crew members. Even when compared to some of the legendary submarines of World War II around this time, such as the 287-foot-long USS Tang, the Scirè was small. What it lacked in size, however, it made up in innovation.

The Scirè began its service for the Italian navy in 1938. It was a short range vessel capable of traversing 3,180 nautical miles at up to 14 knots on the surface and 74 nautical miles at 4 knots while submerged. While not great for long distance missions, this did make the Scirè well-suited for special operations. The Scirè’s existence eventually made sailors docking in British harbors feel uneasy, as it was perfectly outfitted for attacks in shallow waters.

Despite a rough start to its service in the Navy, the Scirè eventually made a name for itself, with the crew adding multiple naval victories under Italy’s belt. Unfortunately, the submarine was met with an untimely end that was shrouded in mystery for a brief period.

The Scirè was part of the Italian Navy’s special forces in WWII

Mircea Moira/Shutterstock

Italy launched the Scirè into service in 1938 but, in August 1940, transferred the submarine to its naval special forces known as X Flottiglia Mas or La Decima. However, the Scirè wasn’t only integrated into this special unit. It also became its spearhead, striking fear into the British Royal Navy stationed in the Mediterranean.

Being part of a special unit meant the Scirè needed some special modifications. First of all, it was painted green to help it blend in with the water under moonlight for night operations. Second, the submarine was originally only armed with six torpedo launchers, so it required a little innovation to become a threat. Engineers modified the tower and removed the 100/47 Mod 35 cannon on its top deck to reduce the submarine’s weight. More importantly, this allowed the submarine to house three watertight tanks on its deck instead.

These little tanks carried a single manned torpedo, steered manually by a pair of divers who could navigate them closer to enemy lines. This helped them avoid radar detection and ensure a direct hit on their targets: unsuspecting docked ships in a harbor.

The submarine deployed human torpedoes

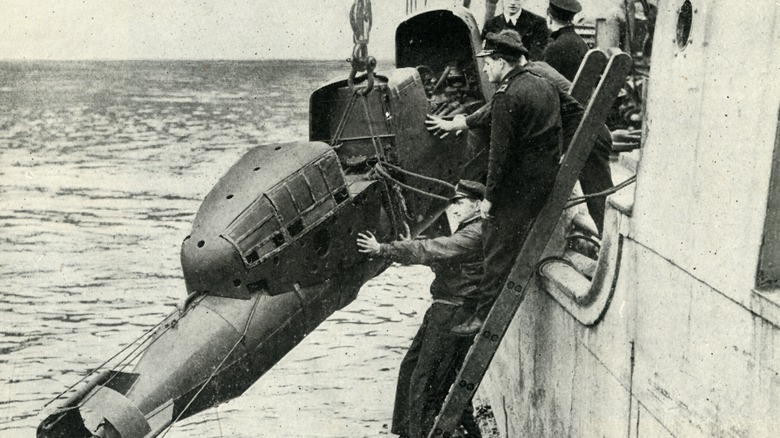

Print Collector/Getty Images

The manned torpedoes, commonly referred to as «human torpedoes» or Siluro a Lenta Corsa (shortened to SLC), were 22 feet long and had two men in diving suits operate them. One man was the pilot while the other removed the warhead from the SLC and attached it to its target. The set up looked similar to a pair of friends riding one of those inflatable bananas behind a boat. When the Scirè arrived to its mission location, the SLC divers would rush to the top deck to mount their SLC and disembark from the submarine. Once about 50 yards from their target, the SLC would submerge and sneakily attack.

The Scirè and its SLCs were so successful that other countries began developing their own, including Germany, Britain, and Japan. Interestingly, World War II wasn’t the first time Italy employed such a tactic. The country utilized a similar weapon in World War I. Even before that, the U.S. utilized a reminiscent design in what is known as the first American submarine, the Turtle, in the American Revolution.

Its early Gibraltar missions flopped

PhotoFires/Shutterstock

The early years weren’t entirely successful for the Scirè. It received its first special mission in September 1940 to attack some ships in the Port of Gibraltar. However, things didn’t go as planned. The first time around, in what was dubbed Operation BG1, none of the ships the Italians expected to be there were docked. They had all set sail to accompany two different missions to protect other ships.

So, in October of the same year, they tried again with Operation BG2. This time, SLC crews got as far as disembarking from the mothership before they were plagued with technical difficulties, forcing them to scrap the entire mission. One team even had to abandon its SLC. Although SLC pilot Lieutenant Birindelli got within 230 feet of his target, he was forced to detonate his warhead from a safe distance before the British could confiscate the device and ended up being captured and held prisoner for the next three years.

While its first few missions were wildly unsuccessful, the crew and Italian Navy did learn a thing or two that allowed them to make progress in future missions. First, they managed to see that they could in fact breach enemy territory and enter a harbor unnoticed. After another subsequent aborted mission, they also decided to start dropping the divers in by plane to get even closer to the target.

The Scirè took down some major British ships

The Mariner 4291/Shutterstock

It might be hard to imagine at this point that the Scirè was fearsome at all. Once Operation BG4 strolled around in September 1941, the submarine’s luck started to turn around. Divers successfully used their SLCs to sink two tankers, Fiona Shell and Denbydale, in the Gibraltar harbor. It also took down a military cargo ship, the Durham. Later that year, the Scirè made way for Alexandria, Egypt, where it used the same tactics to sink the HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Valiant. The former was an important victory because the Queen Elizabeth was the Royal Navy’s flagship of the Mediterranean fleet. Italian opponents in the Mediterranean Sea started to quake at the very thought of the Scirè.

When the Scirè returned to its home port in La Spezia, its commander received a Gold Medal. The ship remained in La Spezia until 1942 when it received a mission to take the port of Haifa. This was an important target for Italy because of the oil refineries there that the British had full control of. Little to Italy’s knowledge, by this point in the war, the British had beefed up its harbor defenses and were on the lookout for the crown jewel of La Decima.

What happened to the Scirè?

The most fascinating bit of trivia about the Scirè is its end. In July 1942, the Scirè departed from the La Spezia base. It had to make a brief pit stop in Lero in early August to pick up some additional crew, but it just stayed there about a week because it had a mission scheduled for August 10, 1942. However, the date of the mission came and went without a single word from the Scirè. The Italian government declared the submarine lost in action by the end of August, but the truth of the matter wasn’t discovered until some time later.

When allied forces communicate with one another, they often use codes to prevent enemy spies from learning valuable information, such as the date of a mission. Unfortunately for the Italian Navy and the crew of the Scirè, British Intelligence intercepted and decoded the message about the mission. The Royal Navy waited for the Scirè in Haifa on the day of the mission and let the submarine approach the port without interruption. Then, a concerted effort between the British Navy and Air Force bombarded the Scirè with depth charges and coastal artillery before it ever had a chance to launch its human torpedoes.

The Scirè homecoming

Sadly, the Scirè did attempt to surrender after depth charges from the HMS Islay struck it, but artillery was already crashing in on its location, making such a gesture impossible. Afterward, the British Navy sent divers down to the wreckage in an attempt to retrieve one or all of the SLCs. After all, they were effective weapons that other countries wanted to employ. Once the British left the area in 1948, the Scirè’s location became unknown to everyone until 1952 when an Israeli naval officer discovered it.

Italy sent a rescue ship to the wreckage in 1984 and retrieved 42 of the 49 crew members along with pieces of the submarine. Those recovered pieces now sit on display at a museum in Augusta, the Arsenal of La Spezia, the Vittoriano in Rome, and Venice. Meanwhile, all of the SLC operators from the Alexandria mission in 1941 had been captured and were only released after Italy surrendered in September 1943. Upon their return to Italy, each operator received the Gold Medal for Military Valor. Today, the WWII era Scirè shares its namesake with the Todaro-class submarine Scirè (S 527) currently used by Italy.