Across the globe this year, from Greece and Portugal to Canada and Hawaii, wildfires have been burning out of control. And as the world heats up, blazes like these are only predicted to get worse and more frequent.

Faced with this imminent threat to lives and infrastructure, authorities are doubling down on tried and tested firefighting techniques. But they are also investing in new, high-tech approaches, pioneered by an emerging segment of ‘firetech’ startups.

Telecoms specialist Dryad Networks, based out of Berlin, is one of them. By tapping AI and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies, Dryad hopes to bring down wildfire detection time from several hours to just a few minutes, giving firefighters time to respond more effectively.

“Today, we still largely rely on human sightings to detect fires. But by the time someone can see a wildfire burning through the canopy it is already very hard to extinguish,” Dryad’s CEO Carsten Brinkschulte tells TNW. “The message we’re getting over and over again is that when it comes to battling wildfires — timing is everything.”

Internet of Trees

Dryad has developed a suite of technologies installed throughout the forest that detect wildfires before they spread — an ‘Internet of Trees’ if you will. Unlike conventional tools, like satellites, cameras, and watchtowers, Dryad’s network doesn’t need to see a fire to know it’s there.

Solar-powered sensors, placed about one per hectare throughout the forest’s understory, detect wildfires in their early smouldering phase by ‘smelling’ tell-tale gases like hydrogen and carbon monoxide in microscopic quantities. They also monitor temperature, humidity, and air pressure.

A built-in machine learning algorithm continually trains the sensors to the specific smell of the forest they are located. This is crucial so that the sensors can, for instance, differentiate between smoke emanating from a diesel truck passing nearby and a legit forest fire.

If the sensors detect a fire ignition they send an alert to a so-called mesh gateway which acts like a network router, sending data from the sensor to a larger, border gateway. These border gateways are situated at the forest edge where there is access to higher bandwidth connections, like 4G or satellite. Border gateways relay potentially life-saving information directly to firefighters, who can interpret the data on a cloud platform.

By working together, this mesh of sensors and gateways enables data to be transmitted over a much greater area and maintain connectivity in dense, remote forests. Dryad’s network also supports a wide range of compatible third-party sensors, not just its own.

“We don’t want a monopoly on this technology,” says Brinkschulte, who describes his company as an impact-for-profit. “We want to stop human-induced fires and their impact on the environment — the tech is almost irrelevant as long as we get results.”

Founded in 2020, Dryad has so far raised €14.5mn in funding and employs some 44 staff from its office in Brandenburg, Germany. The startup already sold 10,000 sensors last year, mainly to public utilities and municipalities in southern Europe, Canada, and the US.

A trial is currently underway in the heart of Eberswalde forest northeast of Berlin, a hotspot for wildfires in the country. More than 400 sensors have been installed in the area.

Across the pond, California’s forestry agency CAL FIRE is trialling Dryad’s tech in thick redwood forests of northern California. Dryad estimates that in the future CAL FIRE could expand this network to cover all of California’s wildfire hotspots for a cost of approximately $29mn. A big number, but one that pales in comparison with the whopping $148.5bn in damages caused by California’s 2018 wildfires alone.

For now, Dryad is building 30,000 sensors and several hundred gateways, with plans for mass rollout next year. Its goal is to deploy 120 million sensors around the world by 2030, to save approximately 3.9 million hectares of forest and prevent 1.7bn tons of CO2 emissions (each year, wildfires emit twice as much CO2 as the aviation industry).

“We want to become the AT&T of the forest,” says Brinkschulte, in reference to the American telecommunications giant.

The rise of firetech

As climate change accelerates, wildfires are spreading faster, burning longer, and raging more intensely. More than 260,000 hectares of land across the EU has already burnt since January — an area the size of Luxembourg.

Faced with this mounting problem authorities and frontline workers are increasingly turning to technologies like AI, drones, infrared cameras, and firefighting robots.

In recent years, numerous startups have popped up like BurnBot, which has built a robot to undertake prescribed burns, or Rain which wants to deploy autonomous helicopters to fight fires. Both Rain and BurnBot are backed by the world’s first fund solely dedicated to firetech, US-based Convective Capital.

In Europe, several fire brigades have been trialling long-range drones like those built by Dutch scaleup Avy to detect wildfires early and help firefighters on the ground track the blaze in real time. Researchers in Portugal are even developing a drone that douses flames from above.

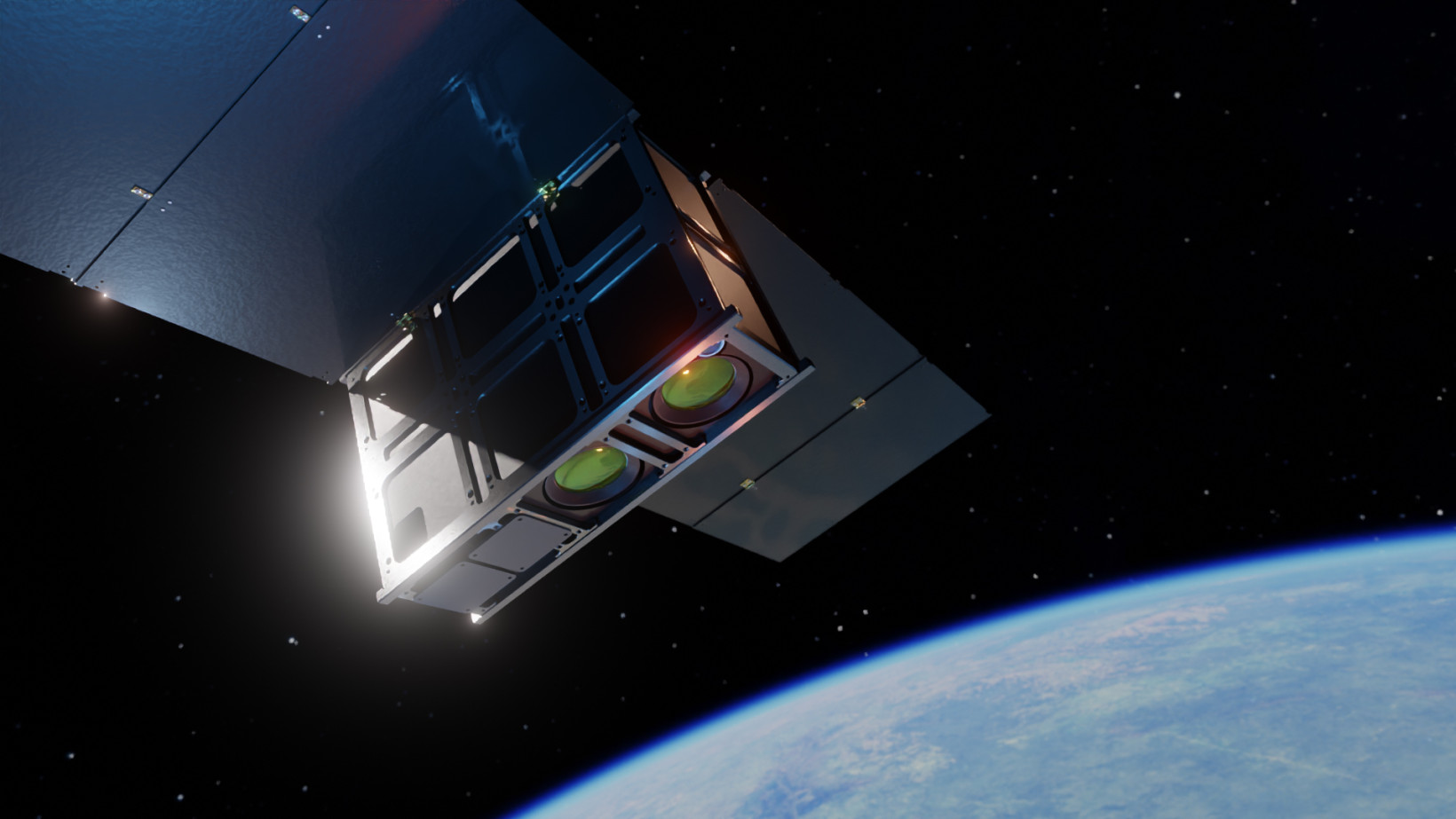

In Germany, OroraTech is building a constellation of AI-powered thermal imaging satellites that it says can detect wildfires within three minutes of ignition, anywhere on Earth. The first satellite was successfully launched into low Earth orbit upon a SpaceX Falcon 9 in June.

On the firefighting side of things, the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme is funding the development of a new type of foam which mixes with water to create a much more effective flame retardant than water alone.

For Dryad’s Brinkschulte, combining and integrating technologies like these is the best way to prevent and control destructive wildfires. “There’s no silver bullet,” he says.

Aside from high-tech solutions, there are equally important approaches like controlled burns to thin the forest floor and good ol’ fashioned citizen awareness.

But scientists agree that without steep cuts to the greenhouse gases causing climate change, wildfires like the ones we have experienced this year will only get worse.